Technology in the publishing industry has changed dramatically in the past twenty years, and yet, I see many submission guidelines out there that haven’t changed with it. Old-fashioned typesetting is extinct for all practical purposes, and digital publishing (for the Kindle, for example) imposes requirements that publishing in paper doesn’t.

To compete and be at the top of your game, you need to understand how the advent of the computer and digital publishing has impacted publishing. Forget typesetting. Forget typewriters. It’s the 21st century.

Many submission guidelines (such as those at the SFWA site, 2005) are written for the novelist submitting a paper manuscript to a publisher that employs a typesetter. They do not serve the short story writer. Short stories have their own requirements, especially in today’s publishing environment.

that are quite up-to-date and good.

#1 Rule to Submission Formatting

Read the guidelines and follow them. Every publisher has a different idea of what they want. If you don’t follow their guidelines, you’re giving them another reason to reject your story.

No More Typewriters!

Many of the old manuscript formatting rules came about because of typewriters and the typesetting tools publishers used. We can let them go now. Typesetting these days is all automated. And most publishers just import your Word doc into software programs like Adobe InDesign or QuarkXPress.

Digital Publishing

Many publishers are formatting for multiple media that can be read on mobile devices (phones & iPads) and hand-held readers like the Kindle, the Sony Reader, etc. These devices require publishers to reformat your story for the different media.

Keeping that in mind, there are things you can do to make it easier on them, and things that will have them tearing their hair out.

A Dozen Tips

To preface, I’ll remind you to always, always read and follow the submission guidelines of the market to which you’re submitting. However, you can put a few best practices into your formatting habits that will endear you to editors and publishers.

It’s in your best interest to learn how to use Word or some other word-processing software like a pro. Get someone to teach you, or use an online tutorial, such as this basic one for Word from Microsoft. For an “Advanced” Word tutorial, check out this Youtube video:

Here’s a checklist of ten formatting habits you can cultivate to make the job of the publisher/editor so much easier (and have them praising your name more often):

- If the publisher requests a particular font, do as they say. But, if not, then use either Courier or Times New Roman, 12-point. Maintain the same size font throughout the manuscript (with the exception of the title). Don’t put in section headers that are larger. If you have headers between sections, keep them the same size and bold them. “Simple” and “functional” are your two keywords.

- If your story is in sections, put a single hashtag between sections. The publisher will probably replace that with something more attractive, but it’s important they know that a section break is happening.

- Add three hashtags at the end of the story. This lets the editor/publisher know that they have the entire manuscript and have reached the end.

- Turn off curly quote marks in Word. These can be a terrible pain in the ass and easily get buggered up. —Instructions—

- Turn off automatic ellipsis creation. Use three periods, not the ellipsis character. —Instructions—

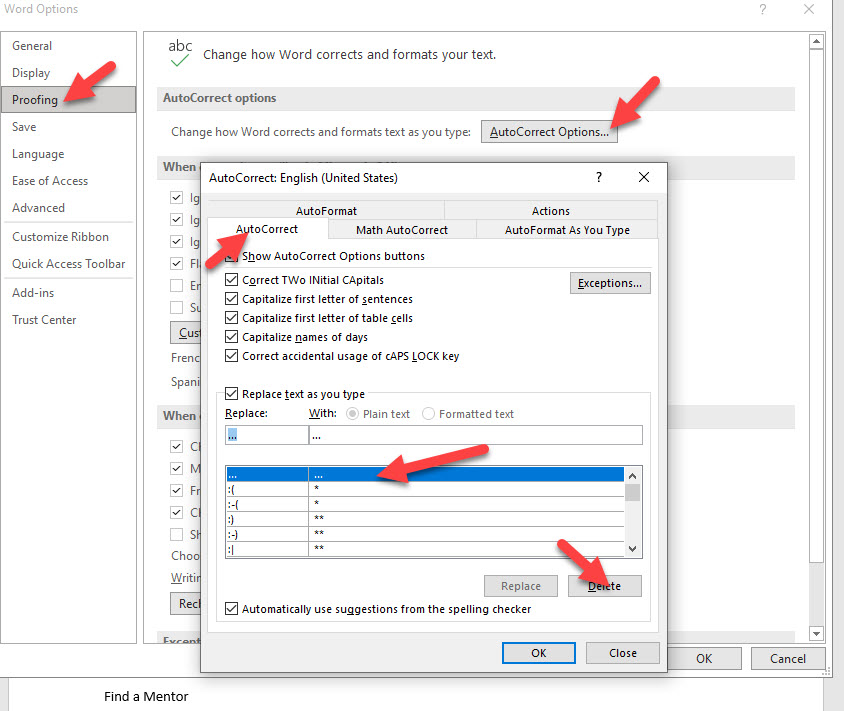

This image shows the Options page. Click “Proofing,” click “AutoCorrect Options,” then make sure you’re on the Autocorrect tab. Look for the ellipsis in the list, highlight it and delete it. Thus, when you type in three periods, it won’t automatically switch to a special character.

- If the guidelines do not request a specific format, use italics for italics. Don’t use underscores for italics. That’s as old-fashioned as putting two spaces between sentences (and has its roots in when our grandparents used typewriters and white-out).

- Do not put two spaces between sentences. Publishers have to strip them out. If you really can’t break the habit of hitting that space bar twice after a period, then make it your habit to do a Search-and-Replace once you’re done. Swap out double spaces for single spaces. It’s fast and easy.

My hero, Grammar Girl, gives an excellent explanation on why we no longer put in two spaces after a sentence.

- Do not manually insert page numbers. Your word processor has an automatic page numbering system that can go in the footer or header. Use that. —Instructions—

- Do not manually insert tabs. Use your paragraph settings to indent that first line. Otherwise, your editor has to go in and delete all those tabs and set the paragraph settings for you. Also, do not manually insert spaces at the beginning of a paragraph.

- Use emdashes, and use them properly. I see so many variations on the emdash and endash. The emdash is the longer one. The endash shorter. The rules are fairly simple once you take the time to learn them, and using them correctly in your manuscript will make you editor’s pet.

- To insert an emdash, all you have to do is hold down the ALT key while you type 0151 on the number pad (not the numbers at the top, but those on the side or in the middle). The endash is your regular ol’ buddy, the dash that’s on your keyboard.

- If you can’t use a real emdash, two endashes are a lamer substitute but won’t get you mocked.

- All style guides, except AP Style, recommend NO space before and after the emdash. This means that, unless you’re writing a journalistic piece, you shouldn’t be putting those spaces in there. For example:

- Correct: The sky was blue—whether we liked it or not—with small fluffy clouds.

- Incorrect: The sky was blue — whether we liked it or not — with small fluffy clouds.

- Learn how to properly use ellipses. We have all gotten into some very bad habits with ellipses because of email, texting, and online chat. Ellipses, however, serve a different role in literary text than they do in casual discussion text.

Grammar Girl gives a great overview of ellipsis use. With short stories (or novels), however, there are a couple of things to especially keep in mind. In fiction, evaluate the voice of what you’re writing. Unless you’re writing in first person, you’ll rarely use an ellipsis outside dialogue because the purpose of the ellipsis is to show hesitating or faltering speech, or skipped words.

Furthermore, it is not a valid substitution for a period. We see this often in email and chat windows, but you’ll rarely use it in literary text except with dialogue, where the speaker trails off and drops words (thus, fitting the skipped word requirement above.) For example:

- Incorrect: John said, “Honey, I’d like to get ice cream before the shop closes…” He stared as an alien burst from his wife’s chest. (The sentence finishes, thus it should be a period, not an ellipsis.)

- Correct: John said, “Honey, I’d like to get ice cream before the…” He stared as an alien burst from his wife’s chest. (Dropped words make the ellipsis appropriate.)

- Consistent formatting is critical. Even if you don’t do it right, do it the same way all the time. It’s those erratic formatting elements that kill your editor/publisher. If you choose to put a blank line between paragraphs (not recommended), then do so exactly the same way each time. Anything you do that makes it easier for your editor/publisher/agent to Search-and-Replace earns you more good karma.

How you format your manuscript isn’t just about making it look good and making it legible. It’s also about preparing it for the transition to a publishable state. If your manuscript requires a ton of work to get it ready, the editor/publisher/agent may pass it up for an equally good story that’s going to be less painful to format.

Do everything you can to improve your chances of:

- Being seen as a professional.

- Being seen as someone who is up-to-date with current word-processing technology.

- Being seen as someone who makes the editor’s/publisher’s/agent’s job easier.